Down syndrome regression disorder (DSRD) is a rare but serious disorder that causes previously high-functioning young people with Down syndrome to suddenly lose their ability to communicate and perform daily living skills. The loss of skills typically occurs over a period of weeks to months.

In Mary Ellen Grover’s case, her regression was severe and lasted eight years until she was able to receive a lifesaving treatment protocol under the care of Zachary Hoy, M.D., pediatric infectious disease specialist at Pediatrix® Nashville Pediatric Infectious Disease. A year into treatment, Mary Ellen has made a full recovery and returned to the lively girl she once was.

Drastic Decline in Health

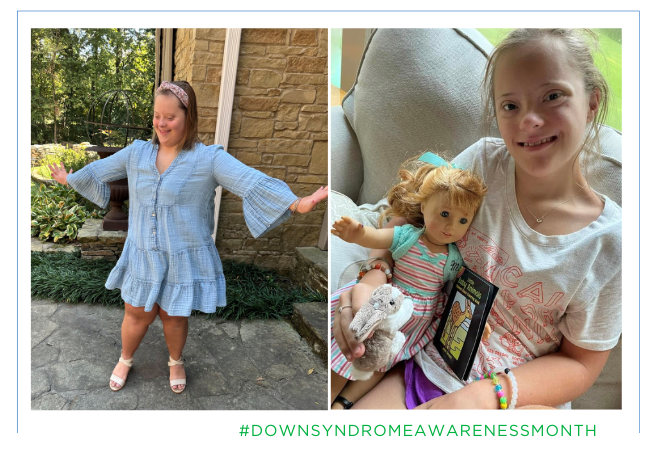

Prior to her regression at the age of nine, Mary Ellen was happy and healthy.

“She was a rather vibrant little girl,” said mom Diane. Just months before she regressed, “she was in a talent show with her best friends singing ‘Let It Go’ on the stage with her arms up in the air. She was very typical for an individual with Down syndrome. We were on a great trajectory.”

Overnight, the Mary Ellen they knew was gone. She became nonverbal and cried a lot. “She was just not the same kid at all,” said Diane.

She also fell critically ill. Her heart rate began to drop dangerously low, and she became oxygen deprived, causing her skin and nail beds to turn gray. She required a heart rate monitor and supplemental oxygen.

“The painful part was that alarm went off all the time,” said Diane. “Her heart rate and oxygen would flip completely. It was probably the scariest thing we ever went through.”

The years ahead were full of many ups and downs, including multiple hospitalizations, as the family desperately searched for answers. Mary Ellen initially saw improvement with a trial of Ativan, an anti-anxiety medication that is commonly used to treat DSRD, for about a year, and then regressed again. This time it was severe, and she had to relearn how to eat and use the bathroom.

“The first eight months was almost like I had an infant,” said Diane. “It was really, really difficult to watch.”

Weaning off the Ativan caused catatonia, inhibiting Mary Ellen’s ability to move normally.

“With catatonia, the difficulty with someone that is nonverbal is that you are trying to figure out what they need, and they get frustrated and may cry or get aggressive because you’re not able to understand them,” said Dr. Hoy.

While DSRD has long been thought to be a psychiatric condition or misdiagnosed as early-onset Alzheimer’s disease or late-onset autism, there is now promising evidence that it may be an inflammatory condition that is potentially curable.

Diane tirelessly researched treatment options and came across a hospital in Boston that was having great success with a therapy called intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG). IVIG is prepared from a pool of immunoglobulins (antibodies) from the plasma of thousands of healthy donors and can boost antibody levels in people with inflammatory diseases. However, it can be difficult to find a provider and obtain authorization.

“It’s expensive medication because it’s a donated blood product and the treatment itself is a pretty large volume of medication,” said Dr. Hoy.

herhand5minutesbeforefirsttreatment%2c(R)herhandtwoweekslater.jpg?width=371&height=393&name=MaryEllenGrover2_(L)herhand5minutesbeforefirsttreatment%2c(R)herhandtwoweekslater.jpg)

Journey to a Cure

Despite Mary Ellen’s deteriorating health, the family made their way to Boston, where they were relieved to officially receive a diagnosis of DSRD. Her entire nervous system was inflamed, and she was put on a pain management plan to help reduce the inflammation. While it immediately had a promising effect, it was only a band aid — not the cure they were so desperately hoping for — and she continued to decline.

“The journey was painfully slow,” said Diane. “It just went on and on and on.”

Ultimately, Mary Ellen was not a candidate for IVIG in Boston and needed to find a provider close to home in Tennessee. Diane happened to see a local friend share on social media that her son was receiving the treatment in Nashville, and Dr. Hoy came into their lives.

“Dr. Hoy immediately got us in,” said Diane. “That was the fastest any doctor had moved.”

Together, they began a yearlong process to gain approval for IVIG, which included submitting hundreds of pages of evidence to justify the need for treatment.

“The biggest hurdle is that a lot of times the newest treatments lag behind in research,” said Dr. Hoy. “The anecdotal evidence comes first.”

The family enlisted help from a non-profit public policy advocacy organization to help guide them in the process. “I always tell parents, trust your instincts,” said Dr. Hoy. “If something doesn’t seem right, you have to keep digging until you feel comfortable that everything’s been done.”

Almost a year ago today, she was finally approved to begin treatment.

“We Have Our Daughter Back”

While IVIG is very much trial and error, Mary Ellen immediately had a positive response.

“It’s difficult because there’s not one test that says, ‘yes, you have this disorder,’” said Dr. Hoy. “The symptoms may fit with that, but you have to jump out on a limb a little bit and try the medication and wait and see what happens.”

Her vitals improved, and she no longer requires a heart rate monitor or daily oxygen. “She has this heathy, vibrant look that we hadn’t seen for years,” said Diane. “She was so pale for so long.”

“The way we see its working is kind of in the day to day, and the parents are obviously the first people to see that because they can communicate their basic needs and do their job like going to school, but also the fun activities,” said Dr. Hoy. “Then, you start to see their personality and they can communicate more.”

Now 18-years-old, Mary Ellen is doing exceptionally well.

“It’s a whole new world,” said Diane. “We’ve got our daughter back. She’s very verbal and she’s swimming and biking.”

Prior to her regression, Diane started a coffee company for Mary Ellen to run in her adult years, and they’re back to making K-Cups.

“She has a much bigger level of independence now,” said Dr. Hoy. “Activities for daily living are much more comfortable, she can communicate and just do her own thing. She’s very independent already but she has that comfort of not having to be tied to oxygen as frequently unless she’s doing certain activities.”

“Dr. Hoy is our hero,” said Diane. “He truly did what no one else was doing in the state of Tennessee, and we needed somebody to do that.”

Learn more about our pediatric services or find care in your area.